Impact of Family Denial of General Anxiety Disorders in Family Members

Gender is correlated with the prevalence of certain mental disorders, including depression, anxiety and somatic complaints.[1] For example, women are more likely to be diagnosed with major low, while men are more likely to be diagnosed with substance abuse and antisocial personality disorder.[i] At that place are no marked gender differences in the diagnosis rates of disorders like schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, and bipolar disorder.[1] [2] Men are at chance to suffer from mail-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to past fierce experiences such every bit accidents, wars and witnessing death, and women are diagnosed with PTSD at higher rates due to experiences with sexual attack, rape and child sexual abuse.[iii] Nonbinary or genderqueer identification describes people who practise not place as either male person or female person.[four] People who place as nonbinary or gender queer evidence increased risk for low, anxiety and postal service-traumatic stress disorder.[5] People who identify as transgender demonstrate increased risk for depression, feet, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[six]

Sigmund Freud postulated that women were more prone to neurosis considering they experienced aggression towards the cocky, which stemmed from developmental bug. Freud'south postulation is countered by the idea that societal factors, such as gender roles, may play a major office in the evolution of mental illness. When considering gender and mental illness, ane must look to both biology and social/cultural factors to explicate areas in which men and women are more likely to develop different mental illnesses. A patriarchal society, gender roles, personal identity, social media, and exposure to other mental wellness risk factors have adverse furnishings on the psychological perceptions of both men and women.

Gender differences in mental health [edit]

Gender-specific take chances factors [edit]

Gender-specific take a chance factors increment the likelihood of getting a particular mental disorder based on i'due south gender. Some gender-specific risk factors that disproportionately affect women are income inequality, low social ranking, unrelenting child care, gender-based violence, and socioeconomic disadvantages.[7]

Anxiety [edit]

Women feel a higher rate of General Feet Disorder (GAD) than men.[8] Women are around 15% more probable to experience comorbidities with GAD than men.[9] Anxiety disorders in women are more likely to be comorbid with other anxiety disorders, bulimia, or depression.[10] Women are two and a half times more likely to experience Panic Disorder (PD) than men.[11] Women are besides twice equally likely to develop specific phobias.[12] Additionally, Social Anxiety Disorder (Lamentable) occurs amidst women more ofttimes than men.[13] Obsessive-compulsive Disorder (OCD) is present among women and men at similar rates, though women tend to have a subsequently onset of symptoms.[14] With OCD, men are more likely to experience more aggressive, sexual-religious, and social impairments while women are more likely to experience fright of contamination.[15]

Gender is non a significant cistron in predicting the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions or cognitive behavioral therapy in treating GAD.[16]

Depression [edit]

Major depressive disorder is twice as common in women compared to men.[17] This increased rate is partially related to women's increased likelihood to experience sexual violence, poverty, and higher workloads.[17] Depression in women is more than likely to be comorbid with anxiety disorders, substance abuse disorders, and eating disorders.[17] Men are less likely to seek treatment for or discuss their experiences with depression.[eighteen] Men are more likely to have depressive symptoms relating to aggression than women.[19] Women are more likely to attempt suicide than men however, more men die from suicide due to the different methods used.[eighteen] In 2019, the suicide rate in the Us was 3.7 times college for men than women.[20]

The presence of a gender bias results in an increased diagnosis of depression in women than men.[xix]

Postpartum low [edit]

Men and women feel postpartum depression. Maternal postpartum depression affects around 15% of women in the Us.[21] Postpartum depression is under-diagnosed.[21] Women experiencing PPD have trouble seeking treatment due to the difficulties of accessing therapy and not existence able to take some psychiatric medications due to breastfeeding.[21] Effectually 8-10% of American fathers experience paternal postpartum depression (PPPD).[22] Risk factors for PPPD include a history of depression, poverty, and hormonal changes.[22]

Eating disorders [edit]

Women found 85-95% of people with anorexia nervosa and bulimia and 65% of those with a binge-eating disorder.[23] Factors that contribute to the gender disproportionality of eating disorders are perceptions surrounding "thinness" in relation to success and sexual attractiveness and social pressures from mass media that are largely targeted towards women.[24] Between males and females, the symptoms experienced by those with eating disorders are very similar such as a distorted torso image.[25]

Contrary to the stereotype of eating disorders' clan with females, men too feel eating disorders. However, gender bias, stigma, and shame lead men to be underreported, underdiagnosed, and undertreated for eating disorders.[26] Information technology has been found that clinicians are non well-trained and lack sufficient resources to treat men with eating disorders.[26] Men with eating disorders are likely to experience muscle dysmorphia.

Gender differences in boyhood and mental health [edit]

Adolescents experience mental illness differently than an developed, equally children'southward brains are nonetheless developing and will continue to develop until effectually the historic period of twenty-five.[27] Children also approach goals differently, which in turn can cause different reactions to stressors such as bullying.[28]

Bullying [edit]

Studies have shown that adolescent males are more probable to exist bullied than females. They have also posed that condition enhancement is one of the main drives of bullying and a 1984 written report by Kaj Björkqvist et al. showed that the motivation of male bullies between the ages of 14-xvi was the status goal of establishing themselves as more dominant.[28] : 113 A smashing'due south gender and the gender of their target tin impact whether they are accepted or rejected by a gender grouping, as a 2010 study by René Veenstra et al. reported that bullies were more likely to be rejected past peer groups who saw them as a possible threat. The study cited an example of a male person unproblematic school bully who was rejected past their female peers for targeting a female person student while a male bully who only targeted other males were accepted past females but rejected by their male peers.[28] : 114

Eating disorders [edit]

The style industry and media have been cited as potential factors in the evolution of eating disorders in adolescents and pre-adolescents. Eating disorders accept been establish to be most common in adult countries and per scholars such as Anne Becker, the introduction of telly has prompted an increase of eating disorders in media-naïve populations.[29] : 1304 [xxx] Females are more probable to have an eating disorder than males and scholars accept stated that this has become more common "during the latter half of the twentieth century, during a period when icons of American beauty (Miss America contestants and Playboy centerfolds) take become thinner and women's magazines have published significantly more articles on methods for weight loss".[31] Other potential reasons for eating disorders among adolescents and pre-adolescents can include anxiety,[32] food avoidance emotional disorder, nutrient refusal, selective eating, pervasive refusal, or ambition loss every bit a outcome of depression.[30]

Suicide [edit]

Data has shown that suicide is the third leading cause of decease in adolescents[33] and that gender has an touch on on the avenue an adolescent may utilize when attempting suicide. Males are known more to use guns in their suicide attempts, whereas females are more likely to cut their wrists or take an overdose of pills.[34] Triggers for suicide among adolescents tin can include poor grades and human relationship issues with significant others or family members.[34] Research has reported that while adolescents share common take chances factors such as interpersonal violence, existing mental disorders and substance corruption, gender specific gamble factors for suicide attempts can include eating disorders, dating violence, and interpersonal bug for females and disruptive beliefs/conduct problems, homelessness, and access to means.[35] They also reported that females are more than likely to attempt suicide than their male counterparts, whereas males are more than likely to succeed in their attempts.[33]

Effects of Social Media on Body Paradigm [edit]

During early boyhood, ane's perception of physical appearance becomes increasingly important, having a significant impact on one'south self-worth.[36] Studies have shown that social media use amongst adolescents is associated with poor body prototype.[37] This is due to the fact that social media utilize increases trunk surveillance. This ways that adolescents regularly compare themselves to the idealized bodies they see on social media causing them to develop self-deprecating attitudes. Both adolescent boys and girls are impacted past the objectifying nature of social media, notwithstanding young girls are more likely to torso surveil due to club'south tendency to overvalue and objectify women.[37] A report published in the Periodical of Early Adolescence found that there is a significantly stronger correlation betwixt self-objectified social media utilise, body surveillance, and body shame among immature girls than young boys. The same studied emphasized that adolescence is an important psychological development flow; therefore, opinions formed about oneself during this fourth dimension can take a pregnant impact on cocky-confidence and cocky-worth.[37] Consequently, low self-esteem can increase ane's take a chance of developing an eating disorder, low, and/or anxiety.[37]

Gender differences post-obit a traumatic event [edit]

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [edit]

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is amidst the most common reactions in response to a traumatic issue.[38] Enquiry has institute that women take college rates of PTSD compared to men.[39] Co-ordinate to epidemiological studies, women are ii to three times more likely to develop PTSD than men.[twoscore] The lifetime prevalence of PTSD is about 10-12% in women and 5-6% in men.[40] Women are too four times more likely to develop chronic PTSD compared to men.[41] There are observed differences in the types of symptoms experienced by men and women.[40] Women are more likely to experience specific sub-clusters of symptoms, such as re-experiencing symptoms (e.yard. flashbacks), hypervigilance, feeling depressed and numbness.[40] [42] These differences are institute to exist persistent across cultures.[39] A meaning take chances factor or trigger of PTSD is rape. In the United States, 65% of men and 45.9% of women who are raped develop PTSD.[43]

Epidemiological studies have institute that men are more likely to have PTSD as a upshot of experiencing combat, war, accidents, nonsexual assaults, natural disaster, and witnessing death or injury.[44] Meanwhile, women are more likely to take PTSD attributed to rape, sexual assail, sexual molestation, and childhood sexual abuse.[44] [45] Still, despite the theorized caption that gender differences were due to different rates of exposure to high touch on traumas such as sexual assaults, a meta-assay found that when excluding instances of sexual assault or abuse, women remained at a greater chance for developing PTSD.[45] Additionally, it has been found that when looking at those who have only experienced sexual assaults, women remained approximately twice every bit probable as men to develop PTSD.[41] Thus, it is likely that exposure to specific traumatic events such as sexual assault only partially accounts for the observed gender differences in PTSD.[45]

Depression [edit]

While PTSD is perhaps the most well-known psychological response to a trauma, depression tin also develop following exposure to traumatic events.[38] Under the definition of sexual assault every bit pressured or forced into unwanted sexual contact, women encounter two times the rate of sexual assail as men.[46] A history of sexual attack is related to increased rates of depression. For example, studies of survivors of childhood sexual assault establish that the rates of childhood sexual set on ranged from vii-19% for women and 3-7% for men. This gender discrepancy in childhood sexual assault contributes to 35% of the gender difference in adult low.[46] Increased likelihood of adverse traumatic experiences in babyhood also explains the observed gender difference in major low. Studies show that women have an increased take chances of experiencing traumatic events in childhood, especially childhood sexual corruption.[47] This gamble has been associated with an increased hazard of developing depression.[47]

As with PTSD, evidence of a biological difference betwixt men and women may contribute to the observed gender departure. Nonetheless, research on the biological differences of men and women who have experienced traumatic events is yet to be conclusive.[46]

[edit]

Risk factors and the minority stress model [edit]

The minority stress model takes into account significant stressors that distinctly bear on the mental health of those who identify equally lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or another non-conforming gender identity.[48] Some risk factors that contribute to declining mental wellness are heteronormativity, discrimination, harassment, rejection (e.g., family rejection and social exclusion), stigma, prejudice, denial of civil and human rights, lack of admission to mental wellness resource, lack of access to gender-affirming spaces (e.one thousand., gender-appropriate facilities),[49] and internalized homophobia.[48] [fifty] The structural circumstance where a non-heterosexual or gender non-conforming individual is embedded in significantly affects the potential sources of risk.[51] The compounding of these everyday stressors increase poor mental health outcomes amid individuals in the LGBTQ+ community.[51] Evidence shows that at that place is a direct association between LGBTQ+ individuals' development of severe mental illnesses and the exposure to discrimination.[52]

In addition, at that place are a lack of access to mental health resources specific to LGBTQ+ individuals and a lack of awareness near mental health conditions within the LGBTQ+ community that restricts patients from seeking help.[50]

Limited research [edit]

At that place is express research on mental wellness in the LGBTQ+ community. Several factors affect the lack of inquiry on mental illness within non-heterosexual and not-conforming gender identities. Some factors identified: the history of psychiatry with conflating sexual and gender identities with psychiatric symptomatology; medical customs's history of labelling gender identities such as homosexuality as an illness (now removed from the DSM); the presence of gender dysphoria in the DSM-Five; prejudice and rejection from physicians and healthcare providers; LGBTQ+ underrepresentation in research populations; physicians' reluctance to ask patients about their gender; and the presence of laws confronting the LGBTQ+ customs in many countries.[52] [53] General patterns such as the prevalence of minority stress have been broadly studied.[48]

There is also a lack of empirical inquiry on racial and ethnic differences in mental health status amongst the LGBTQ+ community and the intersection of multiple minority identities.[51]

Stigmatization of LGBTQ+ individuals with severe mental illnesses [edit]

In that location is a significantly greater stigmatization of LGBTQ+ individuals with more severe conditions. The presence of the stigma affects individuals' access to treatment and is particularly present for non-heterosexual and gender non-conforming individuals with schizophrenia.[52]

Anxiety [edit]

LGBTQ+ individuals are nearly three times more likely to experience anxiety compared to heterosexual individuals.[54] Gay and bisexual men are more likely to have generalized feet disorder (GAD) as compared to heterosexual men.[55]

Depression [edit]

Individuals who identify equally non-heterosexual or gender non-conforming are more probable to experience depressive episodes and suicide attempts than those who identity equally heterosexual.[52] Based solely on their gender identity and sexual orientation, LGBTQ+ individuals face stigma, societal bias, and rejection that increase the likelihood of low.[50] Gay and bisexual men are more likely to have major depression and bipolar disorder than heterosexual men.[55]

Transgender youth are nearly iv times more likely to experience low, as compared to their non-transgender peers.[49] Compared to LGBTQ+ youth with highly accepting families, LGBTQ+ youth with less accepting families are more three times probable to consider and attempt suicide.[49] Every bit compared to individuals with a level of certainty in their gender identity and sexuality (such as LGB-identified and heterosexual students), youth who are questioning their sexuality report higher levels of depression and worse psychological responses to bullying and victimization.[51]

31% of LGBTQ+ older adults report depressive symptoms. LGBTQ+ older adults experience LGBTQ+ stigma and ageism that increment their likeliness to experience depression.[54]

Post-traumatic stress disorder [edit]

LGBTQ+ individuals experience higher rates of trauma than the full general population, the nigh mutual of which include intimate partner violence, sexual assail and hate violence.[56] Compared to heterosexual populations, LGBTQ+ individuals are at ane.6 to iii.nine times greater risk of probable PTSD. One-third of PTSD disparities by sexual orientation are due to disparities in child abuse victimization.[57]

Suicide [edit]

As compared to heterosexual men, gay and bisexual men are at a greater chance for suicide, attempting suicide, and dying of suicide.[55] In the The states, 29% (almost one-third) of LGB youth have attempted suicide at least once.[58] Compared to heterosexual youth, LGB+ youth are twice every bit probable to feel suicidal and over four times equally likely to attempt suicide.[49] Transgender individuals are at the greatest take a chance of suicide attempts.[54] 1-third of transgender individuals (both in youth and adulthood) has seriously considered suicide and one-fifth of transgender youth has attempted suicide.[49] [54]

LGBT+ youth are four times more likely to effort suicide than heterosexual youth.[54] Youth who are questioning their gender identity and/or sexuality are two times more likely to endeavor suicide than heterosexual youth.[54] Bisexual youth accept higher percentages of suicidality than lesbian and gay youth.[51] Equally compared to white transgender individuals, transgender individuals who are African American/black, Hispanic/Latinx, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Multiracial are at a greater risk of suicide attempts.[54] 39% of LGBTQ+ older adults take considered suicide.[54]

Substance corruption [edit]

In the United States, an judge of xx-xxx% of LGBTQ+ individuals abuse substances. This is higher than the nine% of the U.S. population that abuse substances. In improver, 25% of LGBTQ+ individuals abuse alcohol compared to the 5-ten% of the general population.[fifty] Lesbian and bisexual youth have a higher percent of substance use problems as compared to sexual minority males and heterosexual females.[51] Yet, as young sexual minority males mature into early machismo, their charge per unit of substance use increases.[51] Lesbian and bisexual women are twice as likely to engage in heavy alcohol drinking every bit compared to heterosexual women.[54] Gay and bisexual men are less likely to engage in heavy alcohol drinking as compared to heterosexual men.[54]

Substance utilise such as alcohol and drug use amongst LGBTQ+ individuals can exist a coping mechanism in response to everyday stressors like violence, discrimination, and homophobia. Substance use can threaten LGBTQ+ individuals' financial stability, employment, and relationships.[55]

Eating disorders [edit]

The average age for developing an eating disorder is 19 years old for LGBTQ+ individuals, compared to 12–thirteen years old nationally.[59] In a national survey of LGBTQ youth conducted by the National Eating Disorders Association, The Trevor Project and the Reasons Eating Disorder Middle in 2018, 54% of participants indicated that they had been diagnosed with an eating disorder.[sixty] An boosted 21% of surveyed participants suspected that they had an eating disorder.[60]

Various take chances factors may increment the likelihood of LGBTQ+ individuals experiencing disordered eating, including fear of rejection, internalized negativity, postal service-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or pressure to conform with body image ideals within the LGBTQ+ community.[61]

42% of men who experience matted eating identify as gay.[61] Gay men are also 7 times more probable to written report rampage eating and twelve times more likely to written report purging than heterosexual men. Gay and bisexual men likewise experience a college prevalence of full-syndrome bulimia and all subclinical eating disorders than their heterosexual counterparts.[61]

Research has found lesbian women to have higher rates of weight-based cocky-worth and proneness to contracting eating disorders compared to gay men.[62] Lesbian women also experience comparable rates of eating disorders compared to heterosexual women, with similar rates of dieting, binge eating and purging behaviours.[62] However, lesbian women are more probable to report positive body prototype compared to heterosexual females (42.1% vs 20.5%).[62]

Transgender individuals are significantly more than probable than any other LGBTQ+ demographic to report an eating disorder diagnosis or compensatory behaviour related to eating.[63] Transgender individuals may use weight restriction to suppress secondary sex characteristics or to suppress or stress gendered features.[63]

There is limited inquiry regarding racial differences within LGBTQ+ populations as information technology relates to matted eating.[64] Conflicting studies have struggled to ascertain whether LGBTQ+ people of colour experience similar or varying rates of eating disorder proneness or diagnosis.[64]

Causes of gender disparities in mental disorders [edit]

Intimate partner violence [edit]

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a particularly gendered consequence. Data collected from the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS) of women and men aged 18–65 institute that women were significantly more likely than men to experience physical and sexual IPV.[38] According to The National Domestic Violence Hotline, "From 1994 to 2010, about 4 in 5 victims of intimate partner violence were female."[65] The United nations estimates that "35 percent of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or sexual violence past a non-partner (non including sexual harassment) at some point in their lives." [66]

There have been numerous studies conducted linking the experience of beingness a survivor of domestic violence to a number of mental health issues, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, substance dependence, and suicidal attempts. Humphreys and Thiara (2003) affirm that the body of existing research evidence shows a directly link betwixt the experience of IPV and higher rates of self-harm, low, and trauma symptoms.[39] The NVAWS survey constitute that physical IPV was associated with an increased chance of depressive symptoms, substance dependence issues, and chronic mental illness.[38]

A written report conducted in 1995 of 171 women reporting a history of domestic violence and 175 reporting no history of domestic violence confirmed these hypotheses. The study found that the women with a history of domestic violence were eleven.four times more than likely to suffer dissociation, 4.7 times more than probable to suffer anxiety, iii times as probable to suffer from depression, and 2.3 times more likely to have a substance abuse problem.[40] The same study noted that several of the women interviewed stated that they just began having mental wellness problems when they began to experience violence in their intimate relationships.[40]

Some other report institute that in a grouping of women in a psychiatric inpatient hospital ward, women who were survivors of domestic violence were twice as likely to endure depression as those were not.[39] All twenty of the women interviewed fit into a pattern of symptoms associated with trauma-based mental wellness disorders. Six of the women had attempted suicide. Moreover, the women spoke openly of a direct connection between the IPV they suffered and their resulting mental disorders.[39]

In a similar study, 191 women who reported at least one outcome of IPV in their lifetime were tested for PTSD. 33% of the women tested positively were lifetime PTSD, and eleven.iv% tested positive for current PTSD.[67]

Equally far every bit males are concerned, it is estimated that 1 in 9 men experience severe IPV. For men as well, domestic violence is correlated with a higher risk of depression and suicidal behavior.[68]

Sexual violence [edit]

Global estimates published by the Earth Health Organization indicate that virtually 1 in iii (35%) of women worldwide take experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime.[69]

Sexual violence increasingly bear upon adolescent girls who are subjected to forced sex, rape and sexual assault. Approximately 15 million adolescent girls (anile 15 to nineteen) worldwide have experienced forced sexual practice (forced sexual intercourse or other sexual acts) at some point in their life.

Sexual assault, rape and sexual abuse are probable to touch on a women's mental wellness on a short and long-term basis. Many survivors are "mentally marked by this trauma and report flashbacks of their assault, and feelings of shame, isolation, stupor, confusion, and guilt."[seventy] Additionally, victims of rape or sexual assault are at a higher risk for developing PTSD, with the lifetime prevalence being 50% compared to the boilerplate prevalence of 7.8%.[71] Sexual attack is besides associated with college rates of low, self harm, suicide, and disordered eating.[72]

Social Media Pressures and Criticism [edit]

Social media is highly prevalent and influential among the current generation of adolescents and immature adults. Approximately 90% of young adults in the U.s. have and use a social media platform on a regular basis.[73] In terms of social media utilise and body image, boys experience social media as a college positive influence on their body image than girls, who report social media causing more negative furnishings on their body paradigm. Indeed, social media use has a connexion to increased risk for eating disorders in women. Women receive greater amounts of force per unit area and criticism surrounding their concrete appearance, making them more probable to internalize the body ideals that are glorified on social media.

Furthermore, Pro-anorexia communities are widespread among social media platforms which creates an environs that encourages disordered eating behaviors, and uses primarily photos of young women to spread unhealthy letters promoting thinness. Women are more probable to be involved with pro-anorexia communities.[74]

Gender bias in medicine [edit]

The World Health Organization notes gender differentials in both the diagnosis and handling of mental illness.[75] Gender bias observed in diagnostic and healthcare systems (including every bit related to nether-diagnosis, over-diagnosis, and misdiagnosis) is detrimental to the treatment and wellness of people of all genders.[76]

The divergence in diagnosis emerges at an early historic period, with diagnostic rates for children diverging on the basis of gender once children reach schoolhouse historic period.[76] These gendered differentials take been attributed to a variety of factors, including gendered socialization to internalize or externalize symptoms of distress, especially in youth; clinician bias to perceive men as mentally healthy; gendered stereotypes regarding the types of disorders men and women are expected to feel, with emotional issues attributed to women and substance corruption issues to men; and stereotypes and allocation of resources based on, and reifying, these differences.[76] [75] Differential diagnosis rates are also related to differences in aid-seeking or disclosure along gendered lines.[75]

Diagnostic processes may exist influenced by noesis of a patient's sex or gender alone, and male and female patients may receive different diagnoses even when presenting the same symptoms.[76] For instance, even with the aforementioned symptomology or scores according to diagnostic criteria, women are more probable to be diagnosed with depression than men.[75]

Misogynistic Bias in Medicine [edit]

Misogynistic bias has impacted diagnosis and treatment of men and women alike throughout the history of psychiatry, and those disparities persist today.

Hysteria is one example of a medical diagnosis which bears a long history as a "feminine" disorder, whether associated with biological features or with "feminine" psychology or personality.[77] For hundred of years in Western Europe, hysteria was seen as an excess of emotion and a lack of cocky-control, that would generally impact women. The diagnosis was used as a form of social labeling to discourage women from venturing outside of their role, that is a tool to accept control over the increasing emancipation of women.

Another instance in which such disparities emerged is in the use of lobotomies, popularized in the 1940s to treat a variety of psychiatric diagnoses including indisposition, nervousness, and more.[78] Studies have found that United states asylums disproportionately lobotomized women in spite of the fact that men fabricated up the majority of aviary patients.[78] [79] [eighty]

Cisheteronormative Bias in Medicine [edit]

Implicit bias in medicine also bear upon the fashion lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBTQ+) patients, are diagnosed by mental health physicians. Due to internalized societal and medical bias, physicians are more likely to diagnosed LGBTQ+ patients with feet, depression and suicidality.

Gender Normativity and Bias in Medicine [edit]

It has likewise been observed that mental health professionals may pathologize the behaviors of individuals who practise not conform to the practitioner'south gender ethics.[76] Gender ideals accept been found to influence understandings of mental wellness and illness at the stages of diagnosis, handling, and evaluation of symptomology or of treatment.[76]

Socioeconomic status (SES) [edit]

Socioeconomic Status is a global term which refers to a person's income level, education and position in society. Nearly social science inquiry agrees upon the fact that there is a negative relationship between socioeconomic condition and mental affliction, that is lower socio-economical status is correlated with college level of mental affliction. "Researchers have found this human relationship to concur constant for nigh whatever mental illness, from rare conditions like schizophrenia to more common mental illnesses like low."[81]

Gender disparities in socioeconomic status (SES) [edit]

SES is a key gene in determining 1'southward opportunities and quality of life. Inequities in wealth and quality of life for women are known to be both locally and globally. Co-ordinate to a 2015 survey of the U.South Census Agency, in the United States, women's poverty rates are college than men'south. Indeed, "more than than 1 in seven women (virtually xviii.4 million) lived in poverty in 2014."[82]

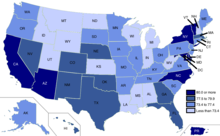

US Gender Pay Gap by state in 2006

When it comes to income and earning power in the United States, women are once again at an economic disadvantage. Indeed, for a same level of pedagogy and an equivalent field of occupation, men earn a higher wage than women. Though the pay-gap has narrowed over time, according U.Southward Census Bureau Survey, it was still 21% in 2014.[83] Additionally, pregnancy negatively affects professional and educational opportunities for women since "an unplanned pregnancies tin can prevent women from finishing their education or sustaining employment (Cawthorne, 2008)".[84]

The touch on of gender disparities in SES on women's mental wellness [edit]

Increasing bear witness tend to show a positive correlation between lower SES and negative mental wellness outcomes for women. Firstly, "Pregnant women with low SES report significantly more depressive symptoms, which suggests that the third trimester may be more than stressful for low-income women (Goyal et al., 2010)."[82] Appropriately, postpartum depression has proven to be more prevalent among lower-income mothers. (Goyal et al., 2010).

Secondly, women are often the main care-taker for their families. As a upshot, women with insecure job and housing experience college stress and anxiety since their precarious economical situation places them and their children at college take a chance of poverty and violent victimization (World Health Arrangement, 2013).

Finally, a depression socioeconomic condition puts women at college risk of domestic and sexual violence, therefore increasing their exposure to all the mental disorder associated with this trauma. Indeed, "statistics show that poverty increases people'due south vulnerabilities to sexual exploitation in the workplace, schools, and in prostitution, sexual activity trafficking, and the drug trade and that people with the lowest socioeconomic condition are at greater risk for violence" (Jewkes, Sen, Garcia-Moreno, 2002).[85]

Biological differences [edit]

Research have been made on the effect of biological differences between male and female on the exposure to both Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Depression.

Mail-traumatic stress disorder [edit]

Biological differences is a proposed mechanism contributing to observed gender differences in PTSD. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has been proposed for both men and women.[86] The HPA helps to regulate an individual's stress response past changing the amount of stress hormones released into the torso, such every bit cortisol.[46] However, a meta-assay found that women have greater dysregulation than men; women have been found to accept lower circulating cortisol concentrations compared to healthy controls, where men did not have this divergence in cortisol.[87] It is also thought that gender differences in threat appraisal might contribute to observed gender differences in PTSD also past contributing to HPA dysregulation.[88] Women are reported to exist more likely to appraise events as stressful and to written report higher perceived distress in response to traumatic events compared to men, potentially leading to an increased dysregulation of the HPA in women than in men.[88] Contempo inquiry demonstrates a potential link between female hormones and the acquisition and extinction of fear responses. Studies suggest that higher levels of progesterone in women are associated with increased glucocorticoid availability, which may heighten consolidation and recall of distressful visual memories and intrusive thoughts.[89] One important challenge for future researchers is navigating fluctuations hormones throughout the menstrual cycle to further isolate the unique effects of estradiol and progesterone on PTSD.

Low [edit]

Expanding on the research apropos the HPA and PTSD, one existing hypothesis is that women are more than likely than men to have a dysregulated HPA in response to a traumatic upshot, like in PTSD. This dysregulation may occur equally a effect of the increased likelihood of women experiencing a traumatic event, every bit traumatic events have been known to contribute to HPA dysregulation.[46] Differences in stress hormone levels can influence moods due to the negative effect of high cortisol concentrations on biochemicals that regular mood such as serotonin.[46] Research has constitute that people with MDD accept elevated cortisol levels in response to stress and that low serotonin levels are related to the development of depression.[46] Thus, it is possible that a dysregulation in the HPA, when combined with the increased history of traumatic events, may contribute to the gender differences seen in depression.[46]

Coping mechanisms in PTSD [edit]

For PTSD, genders differences in coping mechanisms has been proposed as a potential explanation for observed gender differences in PTSD prevalence rates.[forty] Tough PTSD is a mutual diagnosis associated with abuse and trauma for men and women, the "about mutual mental health problem for women who are trauma survivors is depression".[xc] Studies accept found that women tend to respond differently to stressful situations than men. For example, men are more likely than women to react using the fight-or-flight response.[40] Additionally, men are more probable to use problem-focused coping,[twoscore] which is known to subtract the risk of developing PTSD when a stressor is perceived to be within an individual'south control.[91] Women, meanwhile, are thought to use emotion-focused, defensive, and palliative coping strategies.[xl] Every bit well, women are more likely to engage in strategies such as wishful thinking, mental disengagement, and the suppression of traumatic memories. These coping strategies have been found in inquiry to correlate with an increased likelihood of developing PTSD.[41] Women are more than likely to arraign themselves following a traumatic event than men, which has been found to increment an individual's risk of PTSD.[41] In improver, women have been plant to be more than sensitive to a loss of social support following a traumatic event than men.[40] A variety of differences in coping mechanisms and use of coping mechanisms may likely play a role in observed gender differences in PTSD.

These described differences in coping mechanisms are in line with a preliminary model of sex-specific pathways to PTSD. The model, proposed past Christiansen and Elklit,[39] suggests that there are sex differences in the physiological stress response. In this model, variables such as dissociation, social support, and employ of emotion-focused coping may be involved in the evolution and maintenance of PTSD in women, whereas physiological arousal, anxiety, avoidant coping, and use of problem-focused coping may be more than likely to exist related to the evolution and maintenance of PTSD in men.[39] However, this model is only preliminary and further research is needed.

For more virtually gender differences in coping mechanisms, run across the Coping (psychology) page.

[edit]

Each individual has its own way to deal with difficult emotions and situations. Often, the coping mechanism adopted past a person, depending on whether they are safe or risky, volition affect their mental health. These coping mechanisms tend to be developed during youth and early on-adult life. Once a risky coping mechanism is adopted, it is often hard for the private to become rid of it.

Prophylactic coping-mechanisms, when it comes to mental disorders, involve advice with others, body and mental health caring, support and help seeking.[92]

Because of the high stigmatization they often experience in school, public spaces and society in general, the LGBTQ+ community, and more especially the immature people amidst them are less likely to express themselves and seek for aid and support, because of the lack of resources and prophylactic spaces available for them to do so. Every bit a result, LGBTQ+ patients are more than likely to prefer risky coping mechanisms then the rest of the population.

These risky mechanisms involve strategies such every bit self-harm, substance abuse, or risky sexual behavior for many reasons, including; "attempting to become away from or not feel overwhelming emotions, gaining a sense of control, self-penalisation, nonverbally communicating their struggles to others."[93] Once adopted, these coping mechanisms tend to stick to the person and therefore endanger even more than the futurity mental wellness of LGBTQ+ patients, reinforcing their exposure to depression, extreme anxiety and suicide.

See as well [edit]

- Gender bias in psychological diagnosis

- Gender differences in coping

- Gender dysphoria § Classification as a disorder

- Gender in individual mental disorders

- Sexual practice differences in autism

- Sex differences in schizophrenia

- Healthcare and the LGBT community

- Minority stress

References [edit]

- ^ a b c "Gender and women's health". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2007-05-13 .

- ^ Sansone, R. A.; Sansone, L. A. (2011). "Gender patterns in deadline personality disorder". Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (5): 16–xx. PMC3115767. PMID 21686143.

- ^ "Why Women Have Higher Rates of PTSD Than Men". Psychology Today . Retrieved 2019-03-25 .

- ^ Scandurra, Cristiano; Mezza, Fabrizio; Maldonato, Nelson Mauro; Bottone, Mario; Bochicchio, Vincenzo; Valerio, Paolo; Vitelli, Roberto (2019-06-25). "Health of Non-binary and Genderqueer People: A Systematic Review". Frontiers in Psychology. ten: 1453. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01453. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC6603217. PMID 31293486.

- ^ Blueprint for the Provision of Comprehensive Treat Trans People and Trans Communities in Asia and the Pacific Archived 2019-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Health Policy Project. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ Carmel, Tamar C.; Erickson-Schroth, Laura (2016-06-11). "Mental Health and the Transgender Population". Psychiatric Annals. 46 (half dozen): 346–349. doi:10.3928/00485713-20160419-02. ISSN 0048-5713. PMID 28001287.

- ^ "WHO | Gender and women'southward mental health". WHO . Retrieved 2019-03-xx .

- ^ Howell, Heather B.; Brawman-Mintzer, Olga; Monnier, Jeannine; Yonkers, Kimberly A. (March 2001). "Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Women". Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 24 (ane): 165–178. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70212-four. PMID 11225506.

- ^ Yonkers, Kimberly A.; Warshaw, Meredith M.; Massion, Ann O.; Keller, Martin B. (March 1996). "Phenomenology and Course of Generalised Anxiety Disorder". The British Periodical of Psychiatry. 168 (3): 308–313. doi:10.1192/bjp.168.3.308. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 8833684.

- ^ McLean, Carmen P.; Asnaani, Anu; Litz, Brett T.; Hofmann, Stefan G. (Baronial 2011). "Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, form of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness". Journal of Psychiatric Inquiry. 45 (viii): 1027–1035. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006. PMC3135672. PMID 21439576.

- ^ Eaton, W. W.; Kessler, R. C.; Wittchen, H. U.; Magee, W. J. (March 1994). "Panic and panic disorder in the United states". American Journal of Psychiatry. 151 (three): 413–420. doi:10.1176/ajp.151.iii.413. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 8109651.

- ^ Fredrikson, Mats; Annas, Peter; Fischer, HÅkan; Wik, Gustav (January 1996). "Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias". Behaviour Inquiry and Therapy. 34 (1): 33–39. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(95)00048-3. PMID 8561762.

- ^ Asher, Maya; Aderka, Idan M. (Oct 2018). "Gender differences in social anxiety disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 74 (10): 1730–1741. doi:10.1002/jclp.22624. PMID 29667715.

- ^ Mathis, Maria Alice de; Alvarenga, Pedro de; Funaro, Guilherme; Torresan, Ricardo Cezar; Moraes, Ivanil; Torres, Albina Rodrigues; Zilberman, Monica L; Hounie, Ana Gabriela (December 2011). "Gender differences in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a literature review". Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 33 (4): 390–399. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462011000400014. ISSN 1516-4446. PMID 22189930.

- ^ Mathis, Maria Alice de; Alvarenga, Pedro de; Funaro, Guilherme; Torresan, Ricardo Cezar; Moraes, Ivanil; Torres, Albina Rodrigues; Zilberman, Monica L.; Hounie, Ana Gabriela (December 2011). "Gender differences in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a literature review". Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. 33 (4): 390–399. doi:x.1590/S1516-44462011000400014. ISSN 1516-4446. PMID 22189930.

- ^ Cuijpers, Pim; Weitz, Erica; Twisk, Jos; Kuehner, Christine; Cristea, Ioana; David, Daniel; DeRubeis, Robert J.; Dimidjian, Sona; Dunlop, Boadie West.; Faramarzi, Mahbobeh; Hegerl, Ulrich (Nov 2014). "GENDER AS PREDICTOR AND MODERATOR OF Effect IN COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY AND PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR ADULT Depression: AN "Individual PATIENT DATA" META-ANALYSIS: Research Article: Gender as Moderator of Treatment Outcome". Low and Feet. 31 (11): 941–951. doi:10.1002/da.22328. PMID 25407584. S2CID 41401321.

- ^ a b c "Women's increased hazard of low". Mayo Clinic . Retrieved 2021-x-18 .

- ^ a b "NIMH » Men and Depression". www.nimh.nih.gov . Retrieved 2021-ten-18 .

- ^ a b Telephone call, Jarrod B.; Shafer, Kevin (Jan 2018). "Gendered Manifestations of Low and Help Seeking Among Men". American Journal of Men'due south Health. 12 (i): 41–51. doi:10.1177/1557988315623993. ISSN 1557-9883. PMC5734537. PMID 26721265.

- ^ "NIMH » Suicide". www.nimh.nih.gov . Retrieved 2021-10-18 .

- ^ a b c Pearlstein, Teri; Howard, Margaret; Salisbury, Amy; Zlotnick, Caron (April 2009). "Postpartum depression". American Periodical of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 200 (iv): 357–364. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.11.033. ISSN 0002-9378. PMC3918890. PMID 19318144.

- ^ a b Scarff, Jonathan R. (2019-05-01). "Postpartum Depression in Men". Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. xvi (v–half dozen): 11–xiv. ISSN 2158-8333. PMC6659987. PMID 31440396.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2017). "Mental Health Disparities: Women's Mental Health" (PDF) . Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Globe Health Organization (2005). "Gender in Mental Health Enquiry" (PDF) . Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ NIH Medline Plus. "Males and Eating Disorders". Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ a b Strother, Eric; Lemberg, Raymond; Stanford, Stevie Chariese; Turberville, Dayton (Oct 2012). "Eating Disorders in men: Underdiagnosed, Undertreated, and Misunderstood". Eating Disorders. 20 (5): 346–355. doi:10.1080/10640266.2012.715512. PMC3479631. PMID 22985232.

- ^ Lee, Francis S.; Heimer, Hakon; Giedd, Jay North.; Lein, Edward Southward.; Šestan, Nenad; Weinberger, Daniel R.; Casey, B.J. (31 October 2014). "Adolescent Mental Health—Opportunity and Obligation". Science. 346 (6209): 547–549. Bibcode:2014Sci...346..547L. doi:ten.1126/science.1260497. PMC5069680. PMID 25359951.

- ^ a b c Salmivalli, Christina (March 2010). "Bullying and the peer group: A review". Aggression and Fierce Behavior. xv (2): 112–120. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007.

- ^ Patel, Vikram; Flisher, Alan J; Hetrick, Sarah; McGorry, Patrick (April 2007). "Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge". The Lancet. 369 (9569): 1302–1313. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. PMID 17434406. S2CID 34563002.

- ^ a b Becker, Anne E.; Burwell, Rebecca A.; Herzog, David B.; Hamburg, Paul; Gilman, Stephen East. (June 2002). "Eating behaviours and attitudes following prolonged exposure to television among ethnic Fijian adolescent girls". British Journal of Psychiatry. 180 (6): 509–514. doi:x.1192/bjp.180.6.509. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 12042229.

- ^ Keel, Pamela K.; Klump, Kelly L. (2003). "Are eating disorders culture-bound syndromes? Implications for conceptualizing their etiology". Psychological Message. 129 (5): 747–769. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.v.747. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 12956542.

- ^ Thompson, J. Kevin. Smolak, Linda, 1951- (2001). Torso prototype, eating disorders, and obesity in youth : assessment, prevention, and treatment . American Psychological Clan. ISBNone-55798-758-0. OCLC 45879641.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Santrock, John W. (September 2018). Essentials of life-span development (Sixth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN978-1-260-05430-9. OCLC 1048028379.

- ^ a b Santrock, John Due west. (September 2018). Essentials of life-span development (Sixth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN978-ane-260-05430-9. OCLC 1048028379.

- ^ Miranda-Mendizabal, Andrea; Castellví, Pere; Parés-Badell, Oleguer; Alayo, Itxaso; Almenara, José; Alonso, Iciar; Blasco, Maria Jesús; Cebrià, Annabel; Gabilondo, Andrea; Gili, Margalida; Lagares, Carolina (March 2019). "Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies". International Journal of Public Health. 64 (two): 265–283. doi:10.1007/s00038-018-1196-i. ISSN 1661-8556. PMC6439147. PMID 30635683.

- ^ "Competence Considered. Edited past R. J. Sternberg and J. KolligianJr. (Pp. 420; £27.50.) Yale University Printing: London. 1990". Psychological Medicine. xx (4): 1006. November 1990. doi:10.1017/s0033291700037053. ISSN 0033-2917.

- ^ a b c d Fardouly, Jasmine; Vartanian, Lenny R. (June 2016). "Social Media and Body Image Concerns: Electric current Research and Future Directions". Current Opinion in Psychology. nine: 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.005.

- ^ a b c d Coker, Ann L; Davis, Keith E; Arias, Ileana; Desai, Sujata; Sanderson, Maureen; Brandt, Heather M; Smith, Paige H (one November 2002). "Physical and mental wellness effects of intimate partner violence for men and women". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 23 (4): 260–268. doi:ten.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-seven. ISSN 0749-3797. PMID 12406480.

- ^ a b c d eastward f k Humphreys, Cathy; Thiara, Ravi (1 March 2003). "Mental Health and Domestic Violence: 'I Phone call it Symptoms of Abuse'". The British Journal of Social Work. 33 (ii): 209–226. doi:ten.1093/bjsw/33.2.209.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j grand Roberts, Gwenneth L.; Williams, Gail M.; Lawrence, Joan 1000.; Raphael, Beverley (1999-01-13). "How Does Domestic Violence Bear on Women's Mental Health?". Women & Health. 28 (one): 117–129. doi:10.1300/J013v28n01_08. ISSN 0363-0242. PMID 10022060. S2CID 27088844.

- ^ a b c d McLeer, Susan 5; Anwar, A.H. Rebecca; Herman, Suzanne; Maquiling, Kevin (1989-06-01). "Pedagogy is not enough: A systems failure in protecting battered women". Annals of Emergency Medicine. xviii (half dozen): 651–653. doi:ten.1016/s0196-0644(89)80521-ix. ISSN 0196-0644. PMID 2729689.

- ^ American Psychiatric Clan (2017). "Mental Wellness Disparities: Women's Mental Health" (PDF) . Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "Facts & Statistics | Anxiety and Depression Clan of America, ADAA". adaa.org . Retrieved 2019-03-21 .

- ^ a b Kessler, Ronald C. (1995-12-01). "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey". Archives of General Psychiatry. 52 (12): 1048–sixty. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 7492257. S2CID 14189766.

- ^ a b c Tolin, David F.; Foa, Edna B. (2006). "Sexual activity differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of inquiry". Psychological Message. 132 (six): 959–992. CiteSeerX10.1.one.472.2298. doi:ten.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 17073529.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan (Oct 2001). "Gender Differences in Depression" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 10 (5): 173–176. doi:x.1111/1467-8721.00142. hdl:2027.42/71710. ISSN 0963-7214. S2CID 1988591.

- ^ a b Piccinelli, Marco; Wilkinson, Greg (2000). "Gender differences in depression: Disquisitional review". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 177 (half-dozen): 486–492. doi:10.1192/bjp.177.6.486. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 11102321.

- ^ a b c Dentato, Michael (April 2012). "The Minority Stress Perspective". American Psychological Association. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d eastward Human Rights Campaign Foundation (July 2017). "The LGBTQ Community" (PDF) . Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d National Alliance on Mental Illness. "LGBTQ". Retrieved March thirty, 2019.

- ^ a b c d due east f g Russell, Stephen; Fish, Jessica (2016). "Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 12: 465–87. doi:ten.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. PMC4887282. PMID 26772206.

- ^ a b c d Kidd, Sean; Howison, Meg; Pilling, Merrick; Ross, Lori; McKenzie, Kwame (February 29, 2016). "Severe Mental Illness amid LGBT Populations: A Scoping Review". Psychiatric Services. 67 (seven): 779–783. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500209. PMC4936529. PMID 26927576.

- ^ The Shaw Mind Foundation (2016). "Mental Wellness in the LGBT Customs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on Apr 3, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f m h i j American Psychiatric Association (2017). "Mental Health Disparities: LGBTQ" (PDF) . Retrieved Apr i, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Mental Health for Gay and Bisexual Men | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-01-xvi. Retrieved 2019-04-02 .

- ^ Ellis, Amy. "Web-Based Trauma Psychology Resource On Underserved Wellness Priority Populations for Public and Professional Education". American Psychological Association, Trauma Psychology Partitioning.

- ^ Roberts, Andrea L.; Rosario, Margaret; Corliss, Heather 50.; Koenen, Karestan C.; Austin, Southward. Bryn (2012). "Elevated Chance of Posttraumatic Stress in Sexual Minority Youths: Mediation by Childhood Abuse and Gender Nonconformity". American Journal of Public Wellness. 102 (8): 1587–1593. doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300530. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC3395766. PMID 22698034.

- ^ "LGBT Youth | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Wellness | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2019-04-02 .

- ^ "Eating Disorder Bigotry in the LGBT Customs". Center For Discovery. 2018-01-xxx. Retrieved 2019-11-13 .

- ^ a b "Eating Disorders Among LGBTQ Youth: A 2018 National Assessment" (PDF). National Eating Disorder Clan. The Trevor Project. 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c "Eating Disorders in LGBTQ+ Populations". National Eating Disorders Association. 2017-02-25. Retrieved 2019-11-13 .

- ^ a b c French, Simone A.; Story, Mary; Remafedi, Gary; Resnick, Michael D.; Blum, Robert West. (1996). "Sexual orientation and prevalence of trunk dissatisfaction and eating disordered behaviors: A population-based study of adolescents". International Periodical of Eating Disorders. 19 (2): 119–126. doi:ten.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199603)19:ii<119::Aid-EAT2>3.0.CO;2-Q. ISSN 1098-108X. PMID 8932550.

- ^ a b Diemer, Elizabeth W.; Grant, Julia D.; Munn-Chernoff, Melissa A.; Patterson, David A.; Duncan, Alexis East. (2015). "Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Eating-Related Pathology in a National Sample of College Students". Journal of Boyish Health. 57 (2): 144–149. doi:ten.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.003. PMC4545276. PMID 25937471.

- ^ a b Feldman, Matthew B.; Meyer, Ilan H. (2007). "Eating disorders in various lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 40 (iii): 218–226. doi:x.1002/consume.20360. PMC2080655. PMID 17262818.

- ^ "Statistics". The National Domestic Violence Hotline . Retrieved 2019-03-25 .

- ^ "Facts and figures: Ending violence against women". Un Women . Retrieved 2019-03-07 .

- ^ Roberts, Gwenneth L.; Lawrence, Joan One thousand.; Williams, Gail Yard.; Raphael, Beverley (1998-12-01). "The impact of domestic violence on women's mental wellness". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 22 (7): 796–801. doi:ten.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01496.x. ISSN 1753-6405. PMID 9889446. S2CID 752614.

- ^ "NCADV | National Coalition Against Domestic Violence". ncadv.org . Retrieved 2019-04-xviii .

- ^ "Violence against women". www.who.int . Retrieved 2019-03-07 .

- ^ "Sexual Assault and Mental Health". Mental Wellness America. 2017-03-31. Retrieved 2019-03-07 .

- ^ Chivers-Wilson, Kaitlin A. (2020-12-01). "Sexual assault and posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the biological, psychological and sociological factors and treatments". McGill Journal of Medicine. 9 (2). doi:x.26443/mjm.v9i2.663. ISSN 1715-8125. S2CID 18998506.

- ^ Elklit, A.; Shevlin, M. (2011-11-01). "Female Sexual Victimization Predicts Psychosis: A Case-Control Study Based on the Danish Registry Organisation". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 37 (6): 1305–1310. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbq048. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC3196946. PMID 20488881.

- ^ Multidisciplinary social networks research : second International Conference, MISNC 2015, Matsuyama, Nihon, September i-3, 2015. Proceedings. Wang, Leon,, Uesugi, Shiro,, Ting, I-Hsien,, Okuhara, Koji,, Wang, Kai. Heidelberg. 2015-08-24. ISBN978-three-662-48319-0. OCLC 919495107.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Lavis, Anna (2016-05-23), "Alarming Engagements? Exploring Pro-Anorexia Websites in/and the Media", Obesity, Eating Disorders and the Media, Routledge, pp. eleven–35, doi:10.4324/9781315598666-3, ISBN9781315598666 , retrieved 2021-x-25

- ^ a b c d "Gender and women's mental health". www.who.int . Retrieved 2021-10-xviii .

- ^ a b c d due east f Eriksen, Karen; Kress, Victoria Due east. (April 2008). "Gender and Diagnosis: Struggles and Suggestions for Counselors". Journal of Counseling & Development. 86 (2): 152–162. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00492.x.

- ^ Showalter, Elaine (2020-12-16). "four. Hysteria, Feminism, and Gender". Hysteria Beyond Freud. University of California Press. pp. 286–344. doi:x.1525/9780520309937-005. ISBN978-0-520-30993-vii.

- ^ a b Tone, Andrea; Koziol, Mary (2018-05-22). "(F)ailing women in psychiatry: lessons from a painful past". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 190 (twenty): E624–E625. doi:ten.1503/cmaj.171277. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC5962395. PMID 30991349.

- ^ "History of Psychiatry: Mental Ills and Actual Cures: Psychiatric Handling in the Commencement Half of the Twentieth Century". JAMA. 279 (16): 1316. 1998-04-22. doi:10.1001/jama.279.16.1316-JBK0422-two-1. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ^ Braslow, Joel T. (1999-12-01). "History and Evidence-Based Medicine: Lessons from the History of Somatic Treatments from the 1900s to the 1950s". Mental Wellness Services Enquiry. 1 (iv): 231–240. doi:x.1023/A:1022325508430. ISSN 1573-6636. PMID 11256729. S2CID 21448663.

- ^ "Types Of Mental Disease |". Retrieved 2019-03-08 .

- ^ a b Magai, Carol (1992). "Fact Canvas: RU 486". doi:10.1037/e403702005-011.

- ^ Norris, J. Michael (2009). "National Streamflow Information Program: Implementation Status Report". Fact Canvass. doi:10.3133/fs20093020. ISSN 2327-6932.

- ^ "California Reducing Disparities Project". Fact Sail. 2010. doi:10.1037/e574412010-001.

- ^ Jewkes, Rachel; Guedes, Alessandra; Garcia-Moreno, Claudia (2012). "Preventing Kid Abuse and Neglect for the Prevention of Sexual Violence". doi:10.1037/e516542013-033.

- ^ Donner, Nina C.; Lowry, Christopher A. (2013). "Sexual practice differences in anxiety and emotional behavior". Pflügers Archiv: European Periodical of Physiology. 465 (five): 601–626. doi:10.1007/s00424-013-1271-seven. ISSN 0031-6768. PMC3805826. PMID 23588380.

- ^ Meewisse, Marie-Louise; Reitsma, Johannes B.; Vries, Giel-Jan De; Gersons, Berthold P. R.; Olff, Miranda (2007). "Cortisol and post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: Systematic review and meta-assay". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 191 (v): 387–392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024877. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 17978317.

- ^ a b Olff, Miranda; Langeland, Willie; Draijer, Nel; Gersons, Berthold P. R. (2007). "Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder". Psychological Bulletin. 133 (2): 183–204. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.two.183. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 17338596.

- ^ Garcia, Natalia M.; Walker, Rosemary Southward.; Zoellner, Lori A. (2018-12-01). "Estrogen, progesterone, and the menstrual cycle: A systematic review of fear learning, intrusive memories, and PTSD". Clinical Psychology Review. 66: eighty–96. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.005. ISSN 0272-7358. PMID 29945741. S2CID 49429677.

- ^ Covington, Stephanie South. (July 2007). "Women and the Criminal Justice Organisation". Women'southward Health Problems. 17 (iv): 180–182. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2007.05.004. ISSN 1049-3867. PMID 17602965.

- ^ Hundt, Natalie; Williams, Ann; Mendelson, Jenna; Nelson-Grayness, Rosemery (1 Apr 2013). "Coping mediates relationships between reinforcement sensitivity and symptoms of psychopathology". Personality and Private Differences. 54 (6): 726–731. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.028.

- ^ trwd (2017-01-24). "Mental disease is a coping machinery". National Empowerment Center . Retrieved 2019-04-04 .

- ^ "Be true and be you lot: A basic mental health guide for LGBTQ teens" (PDF). Networkofcare.org.

Farther reading [edit]

- Rabinowitz, Sam V.; Cochran, Fredric E. (2000). Men and Depression: Clinical and empirical perspectives. San Diego: Bookish Printing. ISBN978-0-12-177540-7.

External links [edit]

- "Written report Finds Sexual activity Differences in Mental Illness", American Psychological Association

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mental_disorders_and_gender

0 Response to "Impact of Family Denial of General Anxiety Disorders in Family Members"

Post a Comment